Old Sun (2008)

From TRUCK Contemporary Art:

“Old Sun or Natusapi was a chief of the Blackfoot and distant relative. My family has told me that he was a respected leader and distrusted the new comers greatly, he did not want to sign Treaty 7, preferring war to what at the time he considered the end of our way of life. The Blackfoot Reserve #149 or today called the Siksika Nation was divided in half for conversion, the east to the Catholics and the west to the Anglicans. My family camped on the west-end of the reserve and by happenstance claimed by the Anglicans. The school that was built was named Chief Old Sun Residential School, I find it ironic that his namesake was used as it ensured the end of a way of life for many of his descendents; my family members. The institution now called Old Sun College has made the transition from residential school to college yet remains a colonizing symbol for many on my Nation. Over the years, various renovations have created fragments of material culture; I have been privileged to collect many of these fragments.”

Old Sun is a new exhibition of installations by the Saskatoon-based artist, Adrian Stimson. Stimson explores identity, history, and transcendence through the reconfiguration of architectural and natural fragments culled from the relics of the Chief Old Sun Residential School.

The works that appear in Old Sun focus on a particular chapter in Canada’s history of colonialism: the long and unfinished story of the residential school system. This colonial education system—founded and operated through a state-church partnership for over a century until the last school closed in 1996—attempted to “kill the Indian in the child” (Fontaine) by erasing the culture of generations of Aboriginal people: an assimilative practice that is identified in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as cultural genocide.

The title, Old Sun, links this installation-event with Old Sun School, an Anglican residential school founded in 1890 on Stimson’s reserve: the Siksika Nation. Many of Stimson’s family members attended Old Sun School where so many children died of tuberculosis, mumps, cholera, small pox, influenza, measles, and malnutrition: all in the name of civilization. In successive government reports Old Sun School became infamous for its high mortality rates: its buildings were condemned as unsanitary and its overcrowded dormitories were described as providing an ideal incubator for the spread of disease. As Stimson notes, Old Sun School—just an hour’s drive from the Truck gallery—was named after Old Sun or Natusapi, a chief of the Blackfoot and Stimson’s distant relative. “I find it ironic” Stimson says, “that Old Sun School is named after this respected leader who did not want to sign Treaty 7, preferring war to what, at the time, was seen as the end of our way of life. Old Sun School did ensure the end of a way of life for many of his descendants, including my family.”

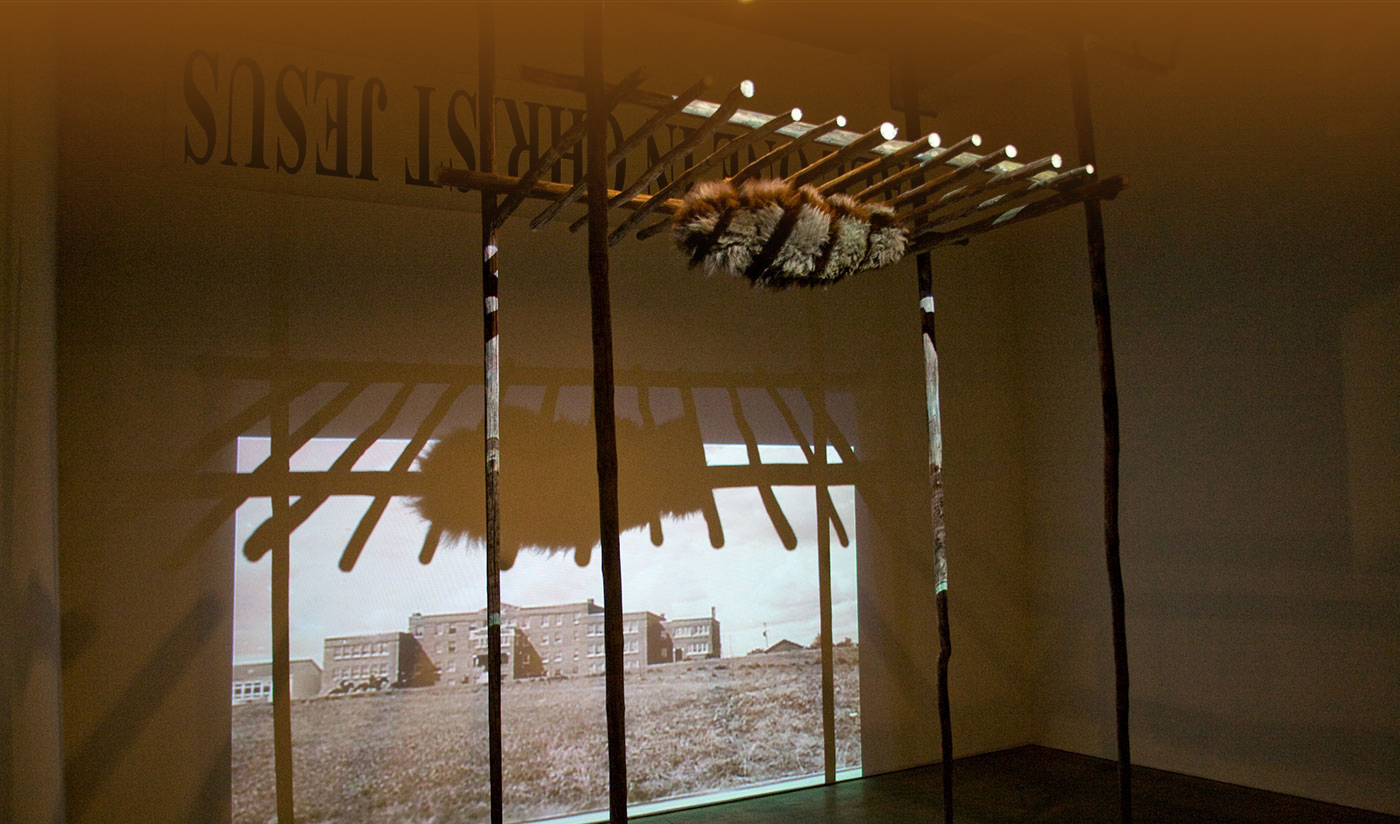

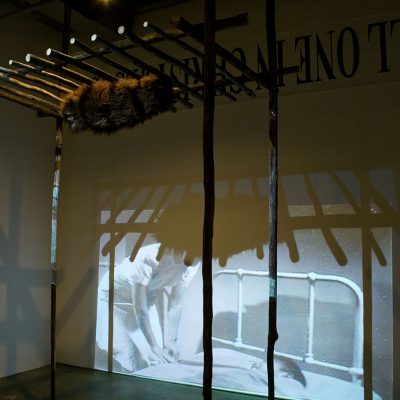

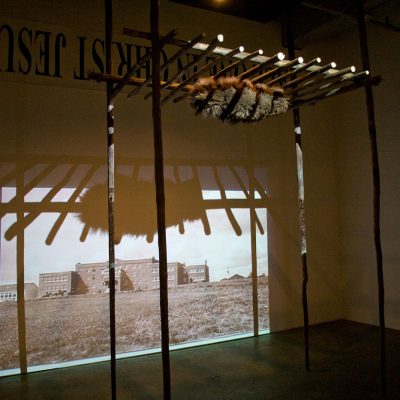

Moving back-and-forth between the installations brings together an accumulation of images: a steel-ribbed sweat lodge lined with scraps of buffalo hide; a classroom light casting shadows that mimic the ‘double-cross’ of the Union Jack; a sleeping figure lying on an infirmary bed wrapped in buffalo fur; the phantom shadow of a flayed buffalo hide; a tall sketchy structure resembling an Indigenous burial platform and a wooden coffin; a small fur-sarcophagus suspended in front of a projection of historical and contemporary images of Old Sun School; and an old Anglican church banner reading: “All one in Christ Jesus.”

Stimson’s installations start from and continually return to the found object: material fragments from Old Sun School including windows, light fixtures, an infirmary bed and black-and-white photographs from an instructor’s personal photo-album. “These fragments,” Stimson notes, “bear witness to the trauma of these schools. They also invoke my relationship to this history. I went to residential school until grade four as a day student. I have a lot of vivid memories that I draw on when I work with these fragments.” Talking about, Old Sun (2005), Stimson says: “The Old Sun light fixture that hangs above the sweat lodge shines downward interrogating the piece. I believe that objects hold energy. This light that once shone above the heads of many children in the school is a witness to cultural genocide. The shadow it creates on the fragments of bison fur is the Union Jack. Shadows of history haunt us but illumination of our history can

enlighten us.” In bringing differing visual elements and signifying systems into juxtaposition, Stimson creates an image-montage that allusively yet insistently draws connections between things that are normally kept apart in the Canadian national imaginary.

Old Sun engages in the exhausting work of mourning yet it is also a story of survival and strength. In his practice as an artist, Stimson repeatedly turns to the figure of the buffalo as a metaphor for spirituality, creativity, and rebirth. In this exhibit, the figure of the buffalo is at once witness, mourner and survivor. As he tells it, “I use the bison as a symbol representing the destruction of the Aboriginal way of life. It also represents survival and cultural regeneration. The bison is central to Blackfoot being.”

In this hauntingly beautiful installation Stimson has created an archive of visual testimony that bears witness to Canada’s colonial past and the “national crime” (Milloy) of the residential school. It is an exhibit that reveals the affective and interrogative force of the visual arts and their ability to make a significant contribution to the urgent task of building an inclusive national imaginary as a process of historical accountability.

-Lynne Bell is a Professor in the Department of Art and Art History and Co-Director of the Humanities Research Unit at the University of Saskatchewan. Her essay on Adrian Stimson’s work, “Buffalo Boy: Camp, Mourning, and the Forgiving of History” appeared in Canadian Art (Summer 2007)

View on TRUCK here.

PRESS

As close to sacred as Canadian art history gets, it invites — in these changing times — some necessary sacrilege. Adrian Stimson is only too happy to provide it: under that old glass dome, a thatch of rough buffalo hide is pinned to the floor by curving steel ribs, cross-hatched into a makeshift sweatlodge roof. The evocation, though, is of prison bars and in more ways than one. Look down and you’ll see the shadow thrown by the light: of the familiar criss-cross of a Union Jack.

The ruling emblem of rigid colonial reign impinging, and darkly, on an Indigenous symbol of sustenance is the point. Stimson, who is from the Siksika First Nation in Alberta, is a seasoned disrupter, and has made a career of performance and installation works that unpack ugly truths about chapters of Canadian history that unspooled alongside the making of blithe icons like Thomson’s.

– Murray Whyte, One thing: Adrian Stimson’s Old Sun reframes history at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Star, April 26, 2018