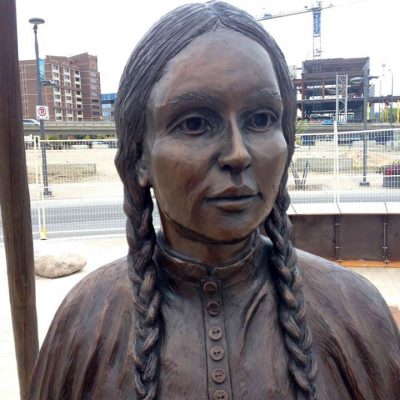

The Spirit of Alliance (2014)

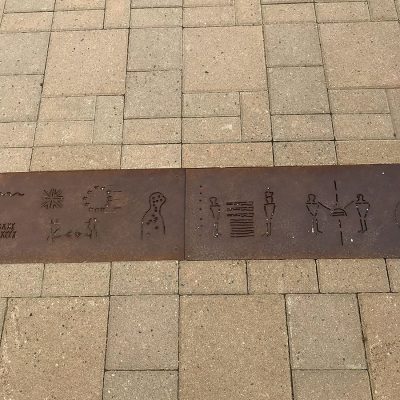

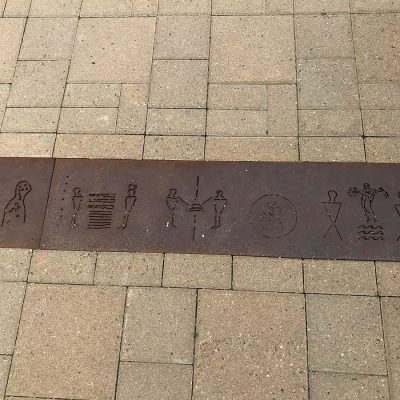

The “Spirit of Alliance” monument located at Saskatoon’s River Landing features the figures of Dakota Chief Wabasha, along with Colonel Robert Dickson, Totowin, and their child Helen. In January 1813, a meeting took place between Robert Dickson and Chief Wabasha. At this meeting, Dickson promised that the British would protect and maintain the First Nations’ territories after the war was over. The promises were exchanged under a tipi, straddling a Medicine Line representing the traditional territories of the Dakota, which extended over the Canadian-US border. Interpretive panels tell the story of the multicultural allies who also participated in the War of 1812 on the side of the British.

Adrian Stimson, Ian (Happy) Grove, Jean-Sebastien Gauthier were the artists for the monument. In 2014, The monument was donated to the City of Saskatoon by Whitecap Dakota First Nation. Prince Edward unveiled the monument at a public event on September 19, 2014. The monument is meant to raise awareness of the legacy of the War of 1812 for Western Canadians. Today, many people including Métis, Francophone, Scottish, Ukrainians, as well as First Nations are descendants of those who fought in the conflict.

Whitecap Dakota First Nation History

Although the War of 1812 is often forgotten, regarded as a stalemate, or misunderstood as an American victory, it played a prominent role in the shaping of Canada as a nation, and remains an important part of the history of the Dakota Oyate.

Many factors are cited as causes of the war: trade restrictions on American goods, the impressment of Americans into the British Navy, or the history of general malcontent between the two nations. Perhaps the most significant factor for First Nations participation was the British promise to maintenance their autonomy and territory. The expansion of American settlement had ushered in an era of harsh and often brutal takeovers of First Nations lands. Clearly, the Dakota had at least as much at stake in the rising conflict with the Americans as the British.

The history of the Dakota Oyate stretches back long before the War of 1812. The Dakota Oyate valued the spirit of alliance. The word “Dakota” means “ally” and “Oyate” means “nation.” They occupied a territory that ranged from modern day Wisconsin through Minnesota, Ontario Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, at times travelling all the way to the Rocky Mountains to hunt and trade.

This spirit of alliance forms the basis of the Dakota’s long-standing relationship with the British Crown, which includes wampum ceremonies in 1761 and a signed Treaty in 1787. The Dakota honored this Treaty as military allies to the British in the American Revolution and in the War of 1812. For their contributions, they were given medals, flags, and promises of protection of their territory and autonomy.

The war officially began in June of 1812. What the Americans thought would be a short conflict continued for two and a half years. Bloody battles and destructive invasions were fought on the Atlantic coast and on the Great Lakes, in modern day eastern Canada and the United States.

For the Dakota, choosing to fight for the British was not simply driven by political alliances with the monarch; it was also necessary for the protection of extended family in the Dakota communities. However important political alliances were between the Dakota and the British, relationships were also formed with fur traders and the like, thereby cementing these alliances in additional ways. Fur trader Robert Dickson married a prominent Dakota woman named Totowin, making Dickson a part of the vast social networks of the Dakota communities. Throughout the War of 1812, Dickson facilitated communication between the Dakota and other Western First Nations and the British forces.

Some of the most successful battles were fought and won with the aid of the Dakota on the Western front, including Fort Michilimackinac, Fort Detroit, and Prairie du Chien. Dakota and other First Nations women were not just passive bystanders of either the alliances themselves, or conflicts in which their families were involved. There is evidence of women’s participation in battles against the Americans.

In spite of the promises made and gifts presented to the Dakota and other First Nations on behalf the British, when it came time to negotiate peace, First Nations were omitted. The Treaty of Ghent was signed in modern day Belgium in 1814, far from the First Nations representatives who had played such a significant part in the conflict itself. The British failed to fulfill their promise to protect the traditional homelands of the Dakota and other First Nations groups, and the Dakota were left sharing territory with their American enemy.

Although the Canada-United States border was established along the 49th parallel in 1818, the Dakota continued to occupy land on both sides of the border—an imaginary line, insignificant to the Dakota and other First Nations people.

After decades of being mistreated by the Americans, the Dakota rose up in a conflict known as the “Minnesota Uprising.” Their leaders made the decision to permanently move northward, seeking peaceful existence in their northern territories amongst their British allies. In 1862, hundreds of Dakota crossed the 49th parallel into their northern territories, along with Chiefs Whitecap, Standing Buffalo, and Littlecrow. They presented their War of 1812 medals and quoted promises of the British, but were confronted by an uninformed colonial administration who had forgotten these solemn promises. Thus, they were mis-labelled “American Indians.”

Some Dakota stayed in present day Manitoba, while others moved west to present day Saskatchewan. Chief Whitecap’s community settled in the Beaver Creek area in 1878. They moved further south to their current location in 1879, where their descendants continue to live today.

The history of First Nations contributions to the War of 1812—like those of the Dakota Oyate—symbolizes the Spirit of Alliance on which this nation was founded.

PRESS & OTHER RESOURCES:

Stephanie McKay, Making of a Monument: Sculpture honours First Nations’ contribution to the War of 1812, Saskatoon Star Phoenix, September 19, 2014

Jean-Sébastien Gauthier, Co-creator on Spirit of Alliance website

CARFAC Saskatchewan Newsletter, November / December 2014 (Downloadable PDF)

Whitecap Dakota First Nation “Dakota Lessons” Information Card (Downloadable PDF)

Opening Ceremony

The Site

The Panels

EAST

View Larger

NORTH

View Larger

SOUTH

View Larger

NORTH

View Larger

PREVIOUS PROJECT | NEXT PROJECT